Joe Abercrombie’s “The Blade Itself”: Sharp, clean and very deadly

Wizards, warriors, weapons and war slither within the 527-page debut novel from Joe Abercrombie that’s stuffed with brilliant relational schemes in a world that feels true and real.

The Blade Itself brandishes a story of shameful rogues meeting vicious bandits, arrogant swordsmen swooning for unorthodox ladies and a kingdom’s torturer suspicious of his very government — among a labyrinth of other complex relations. Here’s a critiqued list of what Abercrombie offers inside this vast, intelligent package.

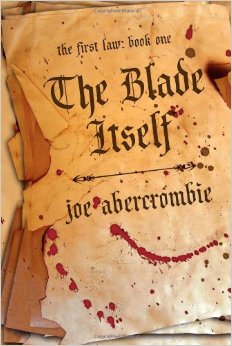

The cover.

Covers are worth far less than their contents, but an equal mastery of art and linguistic skill is a nice feature.

I also want them to look pretty on my bookshelf.

There are a few different covers for TBI, but mine features the words The Blade Itself written in medieval calligraphy on a cover visually manipulated to resemble a battered old stack of papers. A decorative line separates the large title with joe abercrombie at a humbler size, and assumably fresh blood splatters complete it — there’s war inside this novel, physical and mental.

The back cover shows a dim, faded outline of a something like a pentagram, except the Star of David replaces the five-pointed shape. It reappears more prominently on the front cover of the book’s sequel, Before They are Hanged.

It’s gorgeous, symbolic and has a soothing texture like a rubbery plastic (seriously, it feels awesome). My only complaint lies in the “T” in The, which doesn’t seem to crumple though it sits on a ripped and squashed bit of illustrated paper.

The formatting.

Like cover art, aesthetic displeasure in textual formatting won’t destroy a book, but can dim a lot of its goodness. The textual graphics in The Blade Itself aren’t overbearing, but aren’t bland, either. Calligraphic drop caps line the first word of every chapter, and a lovely ink depiction of a sword signifies chapter breaks when a paragraph drops over a page.

His voice.

Abercrombie’s vocabulary is enchanting. It omits no detail, telling everything the reader needs to visualize, whether they’re scenes of a crowded market or a cutthroat battle. His word-canvases soak the reader, but don’t drown him.

And it changes for each character.

The story follows the lives a several different people. Abercrombie’s voice becomes prying and executive as it chronicles the Inquisitor (a decorative title for “torturer”) of Angland, the main kingdom in TBI.

When the scene shifts to a brawling band of hunted convicts, it reads like a pirate. The grandeur and sublime description skills don’t fade, as one would expect if an escaped jail convict were reading. I felt Abercrombie’s talent, but in a bearded, scarred, man-in-hiding type of way.

However, Abercrombie does use “precious few/little” to a noticeable degree in the story, and people hurt in fight scenes usually “gurgle.” A great verb for it, but I saw it so often it felt like it was rubbing against me. Dissatisfying, yes, but these and some other repetitions don’t cloud how unrivaled this book is, and don’t drain any attachment with scenes.

The messages.

The Blade Itself could almost be more of a philosophy textbook than an adventure novel.

Set in a medieval era where family blood is superior to skill and effort, Abercrombie challenges classist views with a perseverant low-class soldier who’s actually able to earn a high title near the end of the novel.

Then Abercrombie introduces a reckless female outsider with tanned skin and a liking for alcohol. She’s the only woman in Angland who says what she thinks — the others busy themselves with proper ladyhood: wigs, tiny hats and keeping silent.

Don’t forget the band of hunted convicts who are the fairest characters in Blade, too.

These three prominent themes are, well, only three. TBI sifts through a great collection of ideas, proposing some, arguing against others.

The story.

A book dries and shrivels when weak morals fill it, but a weak story will discourage the reader from even beginning. Fortunately, The Blade Itself’s plotline is conceivable, structured… and totally awesome.

Most of the reviews for The Blade Itself idolize the fight scenes. This one does, too.

“He pushed himself up, slowly, trying to look as though he was in a daze. Then he let go a roar and spun round, swinging the timber over his head. It broke in half across the masked man’s shoulder with a mighty crack, half of it flying up off the turf and clattering away. The man gave a muffled wail and sank down, eyes screwed shut, one hand clutching at his neck, the other hanging useless, stick dropping from his fingers. Logen hefted the short piece of wood left in his hands and clubbed him across the face with it. It snapped his head back and drove him into the turf, mask half torn off, blood bubbling out from underneath.”

I don’t think I’ve ever read something as fun as that. Of course, this violence isn’t overused, and the book’s bottomless pit of symbolism integrifies any seemingly superfluous thwacks and gurgles.

The visual depictions of land and people are as great as the brawls, too.

The result

If I used a numeric system of grading in this review, it’d be a 9.8/10. But I don’t use a numeric system of grading, so… ha.

Those who escape best in fantasy books should have The Blade Itself (and the whole trilogy) showcased on their bookshelf. The characters are genuine. The setting is real. I can taste the breath of enemies and I can see the beauty of bandit-laden forests and regal-filled kingdoms. I can talk to characters in my thoughts and I’m sure they respond as well.

Want to enter? The book is waiting.