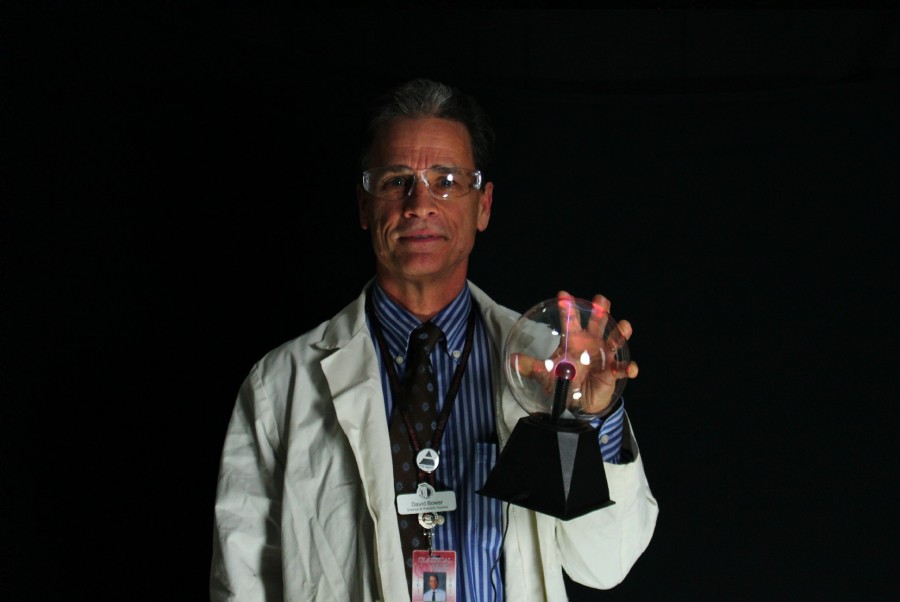

The Science Guys: A look at teachers Andrew Segina and David Bower

Mr. Segina and Mr. Bower explain the roots of their scientific backgrounds and how they apply them to create a unique classroom experience.

In the more obscure corner of the science department, Mr. David Bower and Mr. Andrew Segina serve as connoisseurs of scientific observation and logical methodology. Popping into one of their classrooms causes any prospective student to take a step back and stare in intrigue at the collection of graduated cylinders, thermometers and other sciencey items that grace their shelves. And the instructors themselves have just as much variety, with many an experience and anecdote that adds to their personality.

What do these two have in common? They both teach fields of science that may seem quite obscure to the average high-school student. Classes like Synthetic Biology, AP Chemistry and Earth Science may leave a typical high schooler to scratch their head to try and figure out what they entail. The ability to teach such a niched topic of science comes from a lifetime of appreciation in the field, starting from the early memories of childhood. “One day [my mother] offered to walk me around the yard,” Bower accounted on the time he first learned to appreciate biology. “I wasn’t that impressed with the plants before, but she described the name of every single plant in our yard. And it left such a big impression that it was fun to actually recognize the shape and the texture and smell of plants in their habitat.” It was this observation of the living world that prompted Bower to take a field biology class in high school, and eventually go on to study engineering in college.

With the case of Segina, the decision to major in science was founded more on practicality than passion. “I had three different programs I was interested in,” Segina said. “One was history, one was biology and one was aviation. So I went with the one I thought I could make a living out of”—and that was the biology major he eventually studied.

Later on, both science majors found themselves being hired to teach at Classical Academy High School, each with a unique teaching style that would shape the way students approach the course. For example, in the case of Segina’s Synthetic Biology class, the curriculum is loaded with complex biological sequences and ambitious laboratory experiments that actually result in creating strange and wonderful new organisms. For instance, if you want to create a flower that glows in the dark, a synthetic biology lab would be able to successfully create a bio-luminescent flower using genetic engineering. However, in order to create something like this, students must understand the framework of how certain genetic sequences work.

Segina believes he has a solution: “I found that one of the most effective ways to do that is to create an interesting metaphor, particularly a complex metaphor to describe phenomena that would otherwise require a significant amount of background knowledge in order to have a context for.” Metaphors including the fight between two bunnies over a carrot or a blind man trying to find raisins in oatmeal with a cane may sound completely loony at first, but in a synthetic, biological context, they are actually complex metaphors that accurately describe the functions for a formation of a quinone and for scanning electron microscopy respectively. Both terms might seem insanely complicated to the average reader of this article, but without the metaphors that Segina provides, students of his class would be completely perplexed as to how these sequences work. “None of the kids that were in that discussion will ever forget what a quinone is now because of that,” Segina claims. “Rabbits fighting over a carrot.”

Bower on the contrast teaches two more widely known sciences: physics and earth science, and they have nothing to with with carrots or oatmeal. Instead they explain the basic principles that make up the framework of the world around us. In the case of the former, Bower believes that all other sciences revolve around the observation of physics. “From a certain perspective it is the queen of the sciences” Bower informs. “I just love the fact that physics does enable you to have insight into things as huge as the galaxies and as tiny as quarks.”

One of Bower’s unique takes on a physics lesson includes letting a magnet fall through a copper pipe. The magnet seems to be suspended by an anti-gravity force that makes it fall through much more slowly than if a regular object were put in the pipe. “Physics makes it really clear in a hurry when it seems magical when [the experiment is] happening,” Bower concludes.

Both men have their preferences and differences on what they enjoy teaching, but in the end they are similar in sharing a passion for maybe not the most conventional of sciences, but by far the among the most quirky and obscure of them, making for a unique and unmissable classroom experience for their students.